Helen M Jerome interviews

director of Mondovino

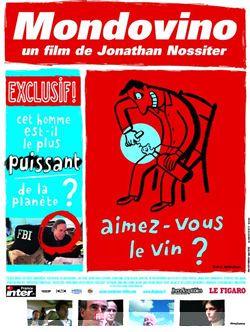

Director Jonathan Nossiter¹s excellent film, Mondovino, fits neatly into the new wave of popular documentaries and reveals a hidden culture.

Director Jonathan Nossiter¹s excellent film, Mondovino, fits neatly into the new wave of popular documentaries and reveals a hidden culture.

The culture in question is the wine business and the film unmasks the intrigue, politics, casual racism and skulduggery involved, as well as globalisation of wine and its consequences. So after just over two hours, viewers will emerge feeling ridiculously well-informed about viniculture and its main players.

US-born Nossiter already has three feature films under his belt (Signs & Wonders, Sunday and Resident Alien) and as a trained sommelier, has also made wine lists for top New York restaurants.

Mondovino was the featured documentary at this year¹s London Film Festival and is released on December 10th 2004. Helen M Jerome quizzed Nossiter over a bottle (of sparkling water, sadly) to find out more about the director’s revealing, non-judgemental and innovative feature.

“I wasn¹t trying to make an encyclopaedic, definitive film about the world of wine,” says Nossiter. “It’s not a film about wine even. I wasn¹t trying to prove a point, I didn’t really care, I was interested in human experience.”

Helen M Jerome: How did you visualise the structure of the film?

- Jonathan Nossiter: “I didn¹t. I¹m always trying to fight against it.

Obviously I worked in the wine trade for a long time and I have feelings and ideas about it, but I was very open and didn’t know where the film was going when I first started out. Like a detective, I tried to follow the clues that would lead me from one person to another. That’s one of the principles.

When you write a script you have to have a narrative which has a certain kind of structure, but what¹s most interesting for me when I’m shooting, is to try and break that structure without betraying the film. It’s the only way of trying to capture something.

It’s something I’ve learned from working with great actors, like Charlotte Rampling and David Suchet, to construct a coherent framework within which they can work emotionally and psychologically, but then they¹re always looking to break your preconception, to release something within that that is true.

The great thing about a non-scripted film like this, with non-actors, is that I don¹t have to make that first step to fight against the structure, I can allow the structure to emerge from the experience.”

With such a loose, fluid idea of what the film was, how did you manage to get it financed?

- “Every film is impossible to make and is a miracle. That¹s true of Hollywood films too. There’s no rational reason why anyone should give anyone else money to make a film. It is a fundamentally irrational act. In the case of this film, because I’d made a bunch of other films, and these people have seen them, we got a tiny bit of money at first and I thought I¹d make a tiny little film over maybe two months. Shooting and cutting it together.

Then it became more interesting than I thought and I got another little chunk of money and started to become slightly obsessed by it. And it took off from there. But the film was made for very little money and was meant to be something interstitial between two features. It never occurred to me that it would take three years of my life, being my next feature. That was a surprise.”

You must have had a lot of material to edit after filming for so long?

- “I had 500 hours of footage at the end and it’s not a record to be proud of. Definitely don’t try that at home! I had to do the editing myself to understand the material and since it’s in five languages. Obviously I had clear memories from the shoot. The narrative of the film was making itself known while I was shooting, so I wasn¹t blind when I sat down.

It took me three or four months just to log the first third of the footage before I could even start to cut. Then I got impatient and started cutting before I’d finished the rest of it. Then I divided my time between cutting and logging for the next year. I had a tremendous assistant, but you have to look at the footage yourself to know. It’s a very peculiar, solitary activity, but I love that.

I love the cut and thrust and action of shooting a film, it’s very non-intellectual, very instinctive, and that’s a tremendous pleasure. But after you’re exhausted by that it¹s a huge boon to be quiet and alone and meditative in the cutting room.

I don¹t understand directors who don¹t want to at least co-edit their own films: a) it’s when you start to construct the language, and b) it provides a depth of reflection about what¹s been shot.”

You know the subject well, but there must have still been things that shocked you.

- “Thankfully almost everything. It’s a film I made in the spirit of delight. I’ve never had so much fun making a film. I hope I never make a film again without that sense of pleasure.”

You seem to speak to all the main players in the wine industry in the film. How did you get such amazing access?

- “To some extent, because it¹s a world that I know, I have certain contacts and friendships from the inside that helped. To another extent it’s simply that wine makes people gregarious. Wine’s just a nice thing, a pleasure. Most people who deal with wine like to speak, they¹re social people, it¹s a social activity.

And once you get a couple of the heavy hitters from the hermetically-sealed world of wine [including the world’s leading wine consultant Michel Rolland, Christie’s wine director Michael Broadbent, and the world¹s most influential wine critic Robert Parker], it¹s hard for other people to refuse. It’s a combination of these things.”

Was it more of a hindrance or a help to know so much about the business?

- “I had enough knowledge of the terrain to be able to navigate though, but not so much that I was weighted down by knowledge. I love wine and have always been intrigued by it and it¹s been an essential part of my life. I¹d worked in the wine trade for a long time, but I don¹t pretend to be a wine expert.

And I brought two friends along who knew nothing about wine. It was a crew of three, me and Uruguayan filmmaker Juan Pittaluga and photographer, Stephanie Pommez. The presence of two talented, intelligent, sensitive friends who knew zero about wine helped to focus the film for people who couldn¹t give a damn about wine and knew nothing about wine. This is absolutely the point of the film.

One thing I can¹t stand about wine is all the snobbery. And the way wine is used as a social weapon. I find it loathsome.”

You also show some of the racial prejudice in various parts of the wine world.

- “Every culture expresses racial insensitivity in some way. In America we’d like to think we¹re democratic and egalitarian and it’s a classless society. And obviously it’s one of the great myths. There are tremendous racial freedoms in America that don¹t exist elsewhere. The presence of a strong black middle class is testament to a certain openness, but then American society is guilty of tremendous racial insensitivity in other areas.

The culture of wine will always reveal fundamental truths about the culture at large.”

What about Robert Parker’s idea of creating a level playing field for wine?

- “It’s a false notion of egalitarianism. To make everything taste the same is not democratic. It’s not egalitarian, I think it’s the imposition of a totalitarian view. Every human being merits respect, every human being is different. The left has been as guilty as the right of bringing uniformity and sterilisation. Hence the presence of George W Bush in America is as much a product of the culture of the left in the US as it is the culture of the right.

This notion that everything is equal and everything should be equal is the most anti-democratic bullshit that I can think of. Democracy is not everyone the same. Everyone has the same rights, everyone has the same right to be respected, but everyone is different. There should be tolerance of diversity. But I think the wine world is also under threat of being blandified and homogenised.”

You also compare wine to humans.

- “Wine is the only thing on earth that resembles people in their infinite variety and complexity. I think, like people, it’s now under threat of being swallowed up by an Aldous Huxleyan homogenisation. We’re under threat of being Prozac-ed into collective submission.”

One of your interviewees (Aniane winemaker Aime Guibert) says that wine is dead.

- “He¹s quite pessimistic. Of course, I don’t agree. The presence of so many vital and courageous people in the wine world is testament to its tremendous vitality. There’s never been so much good wine that exists in the world. So much wine expressive of individual character. But I think its availability is becoming increasingly suspect. Like in cinema, politics, journalism, there’s increasing control of distribution.”

There are a number of uncomfortable revelations in the film. Have you had any threats?

- “Yes, I’ve received quite a few threats. For legal reasons I’m not allowed to say. But unexpected sources. It’s one of the pitfalls and joys of making a documentary.”

What¹s the future for wine making?

- “I’m an optimist, so as long as people are willing to do these things for reasons of personal conviction and essentially as acts of love, which making wine is on some level. And as long as people do that, wine will survive.”

Interview copyright © Helen M Jerome 2004.

More info about the movie at The Internet Movie Database

Reviewer of movies, videogames and music since 1994. Aortic valve operation survivor from the same year. Running DVDfever.co.uk since 2000. Nobel Peace Prize winner 2021.